有关隐喻的绘画

郭笑菲

“绘画一开始就是一种虚拟语气…复制真实不再是绘画的任务。对于我来说,真实存在于 我的选择中,存在于绘画的缝隙里。” 薛若哲的最新系列作品探讨绘画的交流与观看机制。 这组绘画伴随着心理张力,充盈了一股冷峻的荒诞。荒诞来源于他对画面自身语言的篡改, 使得绘画内部的正常逻辑发生了病理性的变异。但若结合绘画中所营造的整体气氛,及其所 折射的心理状态看,这变异又显得合情合理。可以说,这是一组关于“差错”的绘画。吊诡的 空间关系生发于错误的透视、前后等大的人物安排混淆了她们的空间关系;差错玩弄着观者 的眼睛,逼迫他们进行饱含深思却又略显徒劳的凝视。错误的空间与透视造就了神秘荒诞的 氛围,差错在若哲手里成为了一种饱含节制的美学。

诚如马格里特于1937年绘制的那张《不可复制》所示,绘画永远无法复刻现实。但绘画 可呈现的真实可以来源于心理上的体验、对生活的体悟及对周遭环境的感应。在《体操》中, 两个有着几乎相同背影、衣着也一致的女孩站在一个看似空旷、实则封闭的房间中央,她们 规训的身体仿佛被栖息在房间某角落的一股暗藏的力量管制、把控,接受着其虚拟的指令。 画面背景中地面与墙壁的分界线与人物的腰际线发生了重合,不合常理的透视安排致使人物 所处的空间产生了些许倾斜的错觉,加剧了画面空间的抽象与神秘。

相似的人物、一致的角色、不可辨别的身份,及她们与所处空间冰冷又孤独的协议关 系,无不令人想起法国人类学家马克·奥吉(Marc Augé) 对非场所(non-place) 的定义。非场 所是在现代化发展到极致的情形下,于我们现实生活中出现的一种越发遍及的“超现代” (supermodern) 空间。随之而来的是一系列人对空间感知上的转变。当人们进入此类空间 时,他们就由平常的身份统一地转变为了对空间缺乏认同感的寻常过客、顾客或路人、只与 空间维持着单一的契约关系,他们孤独又相似。这种现象在艺术家工作与生活的北京尤甚。 伴随城市士绅化与空间流动性的加强,非场所空间由商场、机场、车站逐渐延续到了艺术家 们的工作室与住所。就像薛若哲所说:“在每个城市,一切都太新了,新得让人觉得不真 实。” 居无定所的生活状态,与各种客观原因导致的生活上巨大的不确定,使那一批生活在 大城市边缘的艺术家从心理上成为了旅人。抽离又抽象的空间,及人与空间、人与人之间隔 离又陌生的关系,所导致的心理紧张感也体现在了薛若哲的《体操》、《不规则四边形的入口》与《或远或近》的非场所化空间里。

Trapeziform Entries 不规则四边形的入口 195x175cmx2,Oil on linen,2017

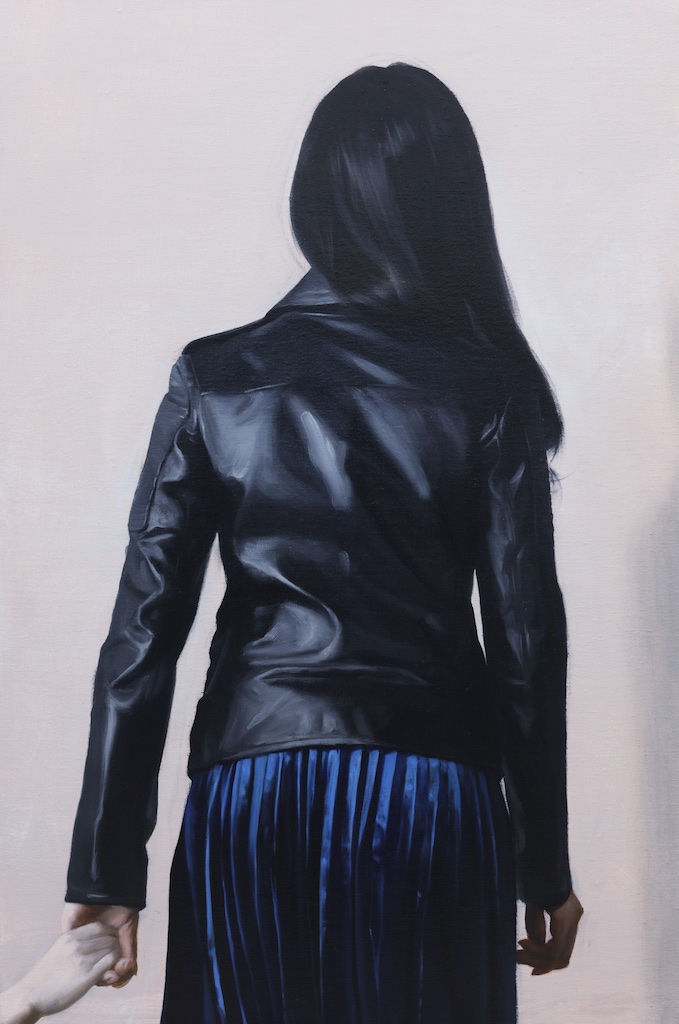

正如对眼睛的欺骗早已不再是绘画美德的批判标准,在薛若哲的这一系列新画中,对眼 睛的欺骗也不再取决于画中透视正确与否,而是由画外空间的光线、画的摆放位置及观者的 观看角度决定。有些绘画中的人物介于画里与画外之间,如《不规则四边形的入口》,画中 的空间通过站立在入又边缘的人物与观者的空间形成了交汇。左边那张画里从下往上看的视 角及人物站立的位置制造了危险的氛围,仿佛这个女人下一秒就要从画的边缘跌落下来。薛 若哲不仅通过对具象绘画传统的扭改,在画面空间中成功营造了一种神秘、不可言说的气氛, 这种气氛还蔓延到了画外、侵入了观者所在的实际空间。走进薛若哲的展览《存在的隐喻》, 观众会马上发现这是一个充满了斥力与荒诞气氛的展览房间——一个被背影包围的房间。挂 在四面墙壁上的肖像画中的人物将后背面对观众、拒绝着观者的凝视与窥探。可以说这些绘 画是反义的肖像画,人物在里面主要起着空间参照,与承载整个绘画机制的作用,其身份及 其它个人信息扑朔迷离。早至2013年,薛若哲画中的人物就开始与墙壁发生关系,墙的存在 给画面内部空间添加了令人窒息的局促感。对于看画的观众而言,他们所面对的实际上也有 两堵墙——画中所绘的墙,及人物如墙一般无法穿透的背影。悬挂着一张张不是肖像的肖像 画空间适当地延伸了画中的那种令人稍感压抑的荒诞气息。

薛若哲的创作历程是一个在绘画语言上删繁就简、“去伪存真”的过程。从《模拟人生》 系列中色彩鲜明却又暗含着隔离感的虚拟游戏环境,到现今由灰墙及深色地板组成、趋向极 简的概念化空间,艺术家掘弃了(同样属于非场所的)媒介环境色彩美好的外衣与具体的人 物身份,只通过他敏锐的感受力保留下那份属于这类空间特有的契约孤独感,与耐人寻味、 充满混淆性的人与空间、人物之间的暧昧关系。画面暗藏的时间性虽也发生了些许的变化, 却亦保留了一定的初衷。

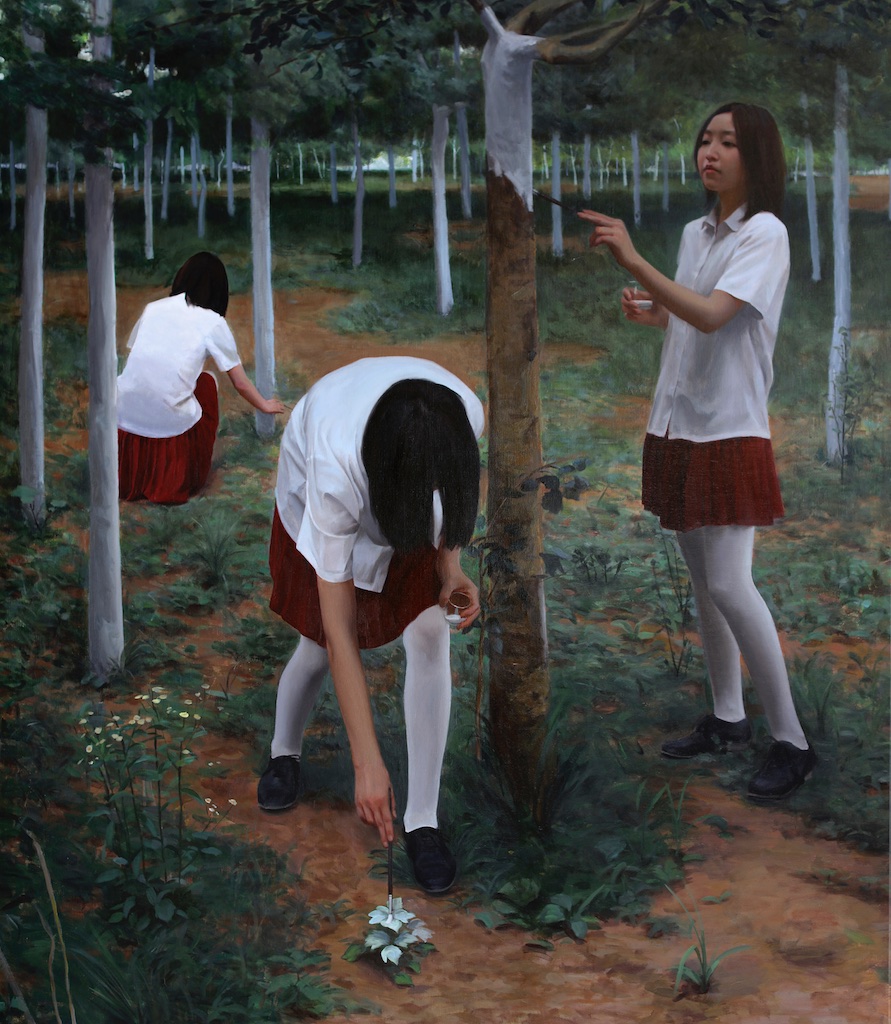

在薛若哲于2011年画下的《白画林》中,同一位穿着相同衣服的模 特暗示这是一个多重的时间画面,它包含了时间的三个瞬间。艺术家利用绘画的虚拟语气, 将这三枚时间晶体收凝在了同一个画面之上,暗示艺术家曾经反复目睹这一荒谬情节的发生, 即既视感的存在。在薛若哲此番的新作《不,再见》与《旅客们》中,艺术家再次将一个动 作的瞬间切割下来、放入画面,但其目的与所呈现的效果则与绘画和观者之间的交流机制有 关。《旅客们》画面中的主人公身体前倾,似正欲向前赶路。这张画挑选了一个从下往上的 观看视角,使观者刚好可以采取从画面左下方伸出来的那只手的位置,并在心理上扮演手的 主人的角色。由于人物的表情无从得知、身体语言也在最大程度上遭到简化,我们无法得知 这是一张牵手行进抑或苦苦挽留的画面。《不,再见》所呈现的也是这样一个语焉不详的画面。这两张画中,绘画所捕捉的时间的单一切片相当于一个脱离语境的悬置符号,其意义随 着观者的自身经历而流变、拒绝稳定。绘画是“断章取义的”,它给予观者多重解读的可能, 这为他们带来不同的心理感受。绘画在此不仅作为浓缩了绘画本身寓意的隐喻而存在,还模 拟了生活与日常关系中的不确定性及暧昧情形下所产生的心理状态。薛若哲利用他“绘画的 缝隙”暗示了一种绘画的真实,与一种存在意义上的真实。《存在的隐喻》亦选择以《不, 再见》中的这个徘徊于拒绝之间、游离于确定之外的暧昧手势作为起始,同时也将它作为了结尾。

White-Painted Forest 白画林 140x160cm,oil on linen, 2011

Paintings about Metaphor

Guo XiaoFei

“Painting speaks in a subjunctive tone from the very beginning…. Reproducing the reality is no longer the task of painting. To me, the truth exists in my choice; it operates in the gap of painting.”

Ruozhe’s latest series explores the communication and viewing mechanisms in painting. Loaded with psychological tension, this group of paintings is charged with a sense of hard-boiled absurdity. The absurdity stems from his peculiar way of tampering with the language of painting, resulting in a pathological mutation in the logic within his paintings. However, if we consider the overall atmosphere that the paintings intend to create, as well as the psychological state they reflect, this variation seems reasonable. It can be said that these are paintings about ‘error’. The strange spatial relations emerge out of the wrong perspective and the arrangement of figures of equal sizes confuse their spatial relations; these mistakes are deceiving to the eyes of the spectator, compelling them to gaze in an attentive way, which is, in the end, futile. The erroneous depiction of space and perspective creates a mysterious and absurd atmosphere; error in Ruozhe’s hands has become a sort of aesthetic with a fine degree of control.

As René Magritte’s 1937 painting Not to Be Reproduced shows, painting can never reproduce reality. However, the truth that painting presents can come from a psychological experience, understanding of life, and the feeling of the immediate environment. In Ruozhe’s Gymnastics, two girls wearing the same uniform look almost identical from behind and are standing in the middle of a seemingly open, yet, in fact, self-enclosed room. Their disciplined bodies seem to be regulated by an invisible power which inhabits some corner of the room, as though they are receiving virtual instructions from it. The line between the ground and the wall in the background of the picture meets the waistlines of the figures. The unconventional arrangement of perspective gives rise to an illusion of a slightly sloping angle of the ground where the characters are situated, which intensifies the sense of abstraction and the mysterious feeling in the pictorial space.

Gymnastics 体操 200x180cm, oil on linen,2017

The identical figures have anonymous roles and unidentifiable identities, and a cold and solitary contractive relationship with their space, all of which evoke the French anthropologist Marc Augé’s definition of the non-place. This place is a kind of super-modern space that emerges in our everyday life in an extreme state of modernism. What follow are a series of changes in people’s perceptions of space. When people enter such spaces, they uniformly experience a transformation from their normal identities into the role of ordinary passers-by, customers or pedestrians who lack a sense of identity and who simply maintain a one-way contractive relationship with the space. They are lonely and similar.

This phenomenon is especially ubiquitous in Beijing, where the artist works and lives. Driven by gentrification and the increasing mobility of space, non-place is gradually extending from shopping malls, airports, and transit stations into artists’ studios and living spaces. Just as Xue Ruozhe said, “In every city, everything is too new to feel real.” Living in a precarious state due to a variety of realistic causes has resulted in huge uncertainty, psychologically turning artists who live on the edges of big cities into travelers. The psychological tension emanating from the abstract and isolated space, and from the alienating and estranged relationships between people themselves and people and space, is also embodied in the non-place space in Xue Ruozhe’s Gymnastics, Trapeziform Entries, and Near, Far.

Near, Far 或远或近137x171cm, oil on linen,2017

Just as tricking the eye is no longer a sufficient criterion for virtue in painting, in Ruozhe’s new series of work, deception of the eyes is no longer contingent upon whether the perspective of the painting is correct or not, but upon the light from outside of the painting; i.e., the way in which the painting is displayed and the viewing angle of the viewer. Some figures are situated between the inside and outside of the picture. For instance, in Trapeziform Entries, the pictorial space intersects with the viewers’ space via the figure standing on the edge of the entrance. The bottom-up angle of viewing and the standing position of the character create a disquieting feeling, as if the woman could fall off the edge of the painting in a second. Xue Ruozhe not only succeeded in creating a mysterious and enigmatic atmosphere in the painted space through a modification of the conventional language of figurative painting, but also extended the atmosphere to the outside of the painting, penetrating the actual space of the viewer.

As one proceeds into Xue Ruozhe’s exhibition entitled The Metaphor of Existence, he or she will immediately realise that the exhibition space is filled with sensations of repulsion and absurdity. The figures in the portraits hanging on the wall have their backs facing the audience, rejecting the viewer’s voyeuristic gaze. We can say that these paintings signify an antithesis to the category of portraiture. The figures mainly serve as a spatial reference to support the function of the pictorial mechanism, while their identities and other personal information remain unknown and indecipherable.

As early as 2013, the characters in Xue Ruozhe’s paintings have had an intriguing relationship with the wall. The existence of walls adds a suffocating, cramped feeling to the internal space of the paintings. The viewers actually face two walls – the wall in the painting and the backs of the figures which are as impenetrable as the wall. As such, the atmosphere of repressive absurdity in the painting is appropriately extended to the space where these non-portraiture portraits are hung.

The process of Ruozhe’s artistic creation is to highlight what is true to painting by simplifying and weeding out the superfluities of its language. From the colourful but estranged virtual gaming environment of the Virtual Life series to the conceptual minimal space which consists of grey walls and dark floors in the current series, the artist has abandoned the seductive colour of the (equally non-place) media environment and the specific identity of characters. What has been preserved through his artistic sensibility is a contractive form of solitariness peculiar to this kind of space, as well as the intriguing and ambiguous relationships between the characters and the space, and between the figures themselves. There is certain change in the temporality embedded in the painting, but it still retains some of the original intention.

In White Painted Forest, which Xue painted in 2011, the repeated use of the same model wearing an identical uniform implies that this is a picture with multiple layers of time; it shows three moments in time. Seizing on the subjunctive tone of painting, the artist crystallised these three moments in time and placed them in the same painting. This suggests that the artist has witnessed the same absurd scene repetitively; that is, it implies the existence of the déjà vu.

Travellers 旅客们105x70cm, Oil on linen,2017

In Ruozhe’s new works, No, Bye and Travelers, the artist once again extracts a specific movement from an action and places it on the canvas; its purpose and the effect presented are related to the communication mechanism between the painting and the viewer. The protagonist in Travelers is leaning forward, seemingly on her way somewhere. The spectator views from the position of the hand that protrudes from the lower left side of the painting; he or she can identify psychologically with the owner of the hand. Since the expression of the characters is hidden from us and the body language has also been simplified to its extreme, there is no way to know if the painting is about walking hand-in-hand or urging someone to stay. No, bye is also presented as a painting with ambiguous meaning.

In these two works, the single slice of the time is not dissimilar to a detached symbol, whose meaning changes with the viewer’s own experience and resists stability. Painting is by definition ‘out of context’, which endows the viewer with the possibility of multiple interpretations, evoking a variety of psychological experiences. The painting here not only serves as a metaphor for the sake of enriching the meaning of painting itself, but also simulates a psychological state arising from uncertain and confusing situations in everyday life. The truthfulness of painting and the truth in its existential sense have been played out within what Xue Ruozhe suggests is “the gap of painting.” Not by coincidence, The Metaphor of Existence also starts with an ambiguous gesture, swaying between refusal and affirmation in the painting No, bye.

No,bye不,再见 34x47cm, oil on linen,2017