李佳

Li Jia

对一位当代画家来说,这或许不是一个最好的时代:最近的一个多世纪以来,在“艺术”界域之内似乎还没有哪件事情像绘画这样被反复宣判死亡,又一再被肯定重生。

今天的绘画早就不再是一个大写的专名,它现在游移在各种关于媒介的、概念的、行为的、历史的……话语平面之间,被迫在变动了的文化地层中重新勘定自己的位置。后者在被称作现代性的地质分界之上,还在持续经历褶皱、裂变、迁移和沉积。在今天,选择成为一名严肃画家,意味着要面对绘画所有的历史,承认一切已经过去的同时,继续这古老的实践,在这条充满重复、排除和否定的窄路上走下去。今天的画家因此总是不可避免地一次又一次回到那个最初,也是最终的问题:如何在绘画的内部将之重新启动,将之再度发明出来,并不断给予它新的定义和可能。

This is perhaps not the best of times for a contemporary painter: since the last century, it seems no artistic medium other than painting has been so often condemned to death and reborn.

Painting has long since ceased to be a proper noun with a capital letter; it now moves between various planes of discourse on media, concepts, behaviour, and history …… and it is forced to reconfigure its position in a shifting cultural terrain. The latter continues to undergo folds, fissures, migrations, and deposits above the geological divide known as modernity. Choosing to be a serious painter today means confronting all of painting’s history, recognising that everything has passed while continuing this ancient practice on a narrow path full of repetition, exclusion, and denial. Today’s painters therefore always return again and again to that initial and ultimate question: how to reactivate painting within a painting, to reinvent it, and constantly give it new definitions and possibilities.

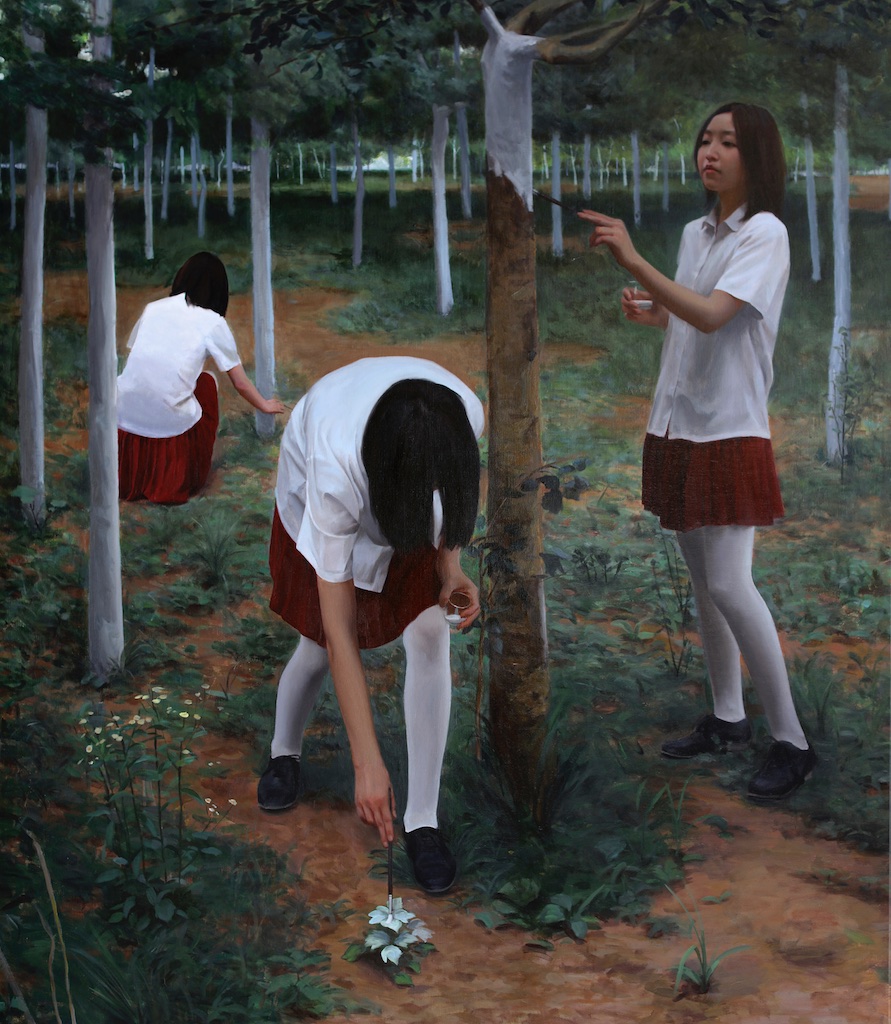

White-Painted Forest 白画林,2011. Oil on linen, 160x140cm

在薛若哲早期的画面中,作为画家的自觉和对于绘画的追问,以不动声色的面目初次显示出来。完成于2011年的《白画林》是他在中央美术学院油画系毕业创作前夕绘制,初看上去,这是一幅写实之作。远景是一片树林,中景和近景处,林间草地上,三位体态、衣着几乎相同的年轻女性围绕树干或立,或蹲,或俯身。女性的肢体、姿态遵循着呼应与韵律的古典构图原则,三个人各伸出一只裸露的肉色手臂,牵引观者的视线从右侧向上,再行降至中景,最后落在最前方女孩向下伸去的指尖。而远处树林直立排布的白色枝干,也在前景两位女孩穿白色丝袜的小腿得到呼应和延续。一双训练有素、阅览过艺术史和熟习各类风格的批评之眼,可能会在最初的一瞥后得出这样的印象,在这里似乎包含了各种已被绘画自身的历史加以质疑的经典写实法则:通过遵循构图和设色的规律,来布置氛围和经营叙事,让再现的对象在画幅边框之内达成自洽和统一。然而,在目光稍作停留之后,这双眼睛不免困惑地眨动:画中人正在用蘸着白颜料的画笔将树干和草丛涂白,而远处丛生的白色枝干也在暗示这并非一片现实中普通的白桦林,而是艺术家在标题中刻意混淆理解的“白画林”。白桦与“白画”的同音双关是否在喻示:如果画中的这一片树林是画中人用白色颜料画出来的,再进一步推测也并非没有道理——这幅画的作者会否也正在画中,我们所看到的,是否正是画中的女孩挥动手中笔,让包括树木、草地和自身从虚空画布上显这里形的过程?甚至,女孩们衬衫和袜子的白色,同树干的白色几乎完全相同,这也暗示了它们来自同一块色板上的颜料。直到这时,我们才会明白这幅画其实并非关于树林或女孩,也非关写实或具象的传统再现原则,在,形象、姿态和场景只是启动绘画机器的必要动力,而真正在这里运作和产生意义的,是绘画实践本身。“画”于是成为一个动词,将画布的平面、同想象的平面、现实的平面、形状和线条的平面缝合在一起。而艺术家在这复合平面上的工作,莫如说是尝试用绘画来指涉和呈现绘画自身,即,绘画如何可以暗示,甚至述说它自己。

In Xue Ruozhe’s early paintings, his self-consciousness as a painter and his inquisitiveness about painting are unabashedly revealed for the first time. Completed in 2011, “White Painted Forest” was painted before he graduated from the Oil Painting Department of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, and at first glance, it appears to be a realistic work. In the distance, there is a forest, and when we move our eyes to the foreground, on the grass, three young women with almost identical physique and clothes are standing, squatting, or bending around a tree. The women’s limbs and gestures follow the classical compositional principles of echo and rhythm, with each of the three holding out an arm, drawing the viewer’s eye upwards from the right, then downwards to the middle, and finally onto the fingertips of the girl in the foreground, who is stretching downwards. The white branches of the distant forest are echoed and repeated in the white stocking-clad calves of the two girls in the foreground. A trained critical eye, well-read in the history of art and familiar with various styles, may, at first glance, come away with the impression that there seems to be a variety of classic realistic rules that have been challenged by painting history: by following the rules of composition and colouring to set the atmosphere and run the narrative, the reproduced objects reach a self-sustaining unity within the canvas. However, after a moment, these eyes blink in confusion: the artist is painting the trunks of the trees and the grass with a brush dipped in white paint, and the white branches in the distance suggest that this is not an ordinary birch forest, but a “White Painted Forest”, which the artist deliberately alludes to in the title. Is the homophonic pun of “white birch” and “white painting” in Chinese a metaphor? If this forest in the painting was painted by the artist with white paint, it is not unreasonable to ask ourselves further: could the artist of the painting also be in the painting, and is what we are seeing the same as the girls in the painting? Is it possible that the girls in the painting with brushes in their hands are the ones making the trees, the grass, and painting themselves on the empty canvas? Even the white of the girls’ shirts and stockings is almost identical to the white of the tree trunks, suggesting that it is from the same palette of paint. It is not until this point that we realise that the painting is not about the woods or the girls, nor is it about the traditional principles of realistic or figurative reproduction, where the image, the gesture, and the scene are only the necessary motivation to start the painting machine, but that it is rather the action of painting itself that really operates and produces meaning here. “Painting” thus becomes a verb, stitching together the plane of the canvas, the plane of the imagination, the plane of reality, and the plane of shapes and lines. The artist’s work on this composite plane is nothing less than an attempt to use painting to refer to and present painting itself, i.e., how painting can imply, or even speak, about itself.

也正是在这个意义上,《白画林》成为艺术家摸索数年之后重新回归的一个起点。虽然它的得来更多出自偶然:构图场景来自艺术家在美院附近小区闲逛时的无意一瞥,而画中三位看上去极为相似的女孩,也是因为当时的他难以雇佣三位模特,而不得已将同一位模特画了三遍,并将其中二位的脸处理成颔首而隐藏的样子。直到数年后,当“复数”系列开始成为他创作的一条主线,同一画面中主要形象的重复和偏移逐渐成为成为组织画面和构筑(同时也是抵牾和模糊)其解读路径的方法,其中的意味才更加充分地显露出来:与其说薛若哲的画面中总会有极为相似的形象相伴相生,不如说那是同一形象在反复地出现、映照和比邻。

It is also in this sense that White Painted Forest became a starting point after several years of painting practice. Yet it came about more by chance: the composition of the scene came from the artist’s unintentional glance when he was wandering around the neighbourhood near the Academy, and the three girls in the painting, who look very similar to each other, also came about because it was difficult for him to hire three models at that time, so he had to paint the same model three times and make two of them look like they were hiding their heads. It was not until a few years later, when the “Plural” series began to become a main body of his work and the repetition and offsetting of the main figures in the same painting gradually became a way of organising the picture and simultaneously constructing, contradicting and blurring its path of interpretation, that the meaning of the series was more fully revealed: rather than saying that Xue Ruozhe’s pictures are always accompanied by extremely similar images, Xue Ruozhe’s paintings have always been accompanied by extremely similar images, it is more fitting to say that the same character appears over and over again, mirroring and neighbouring itself.

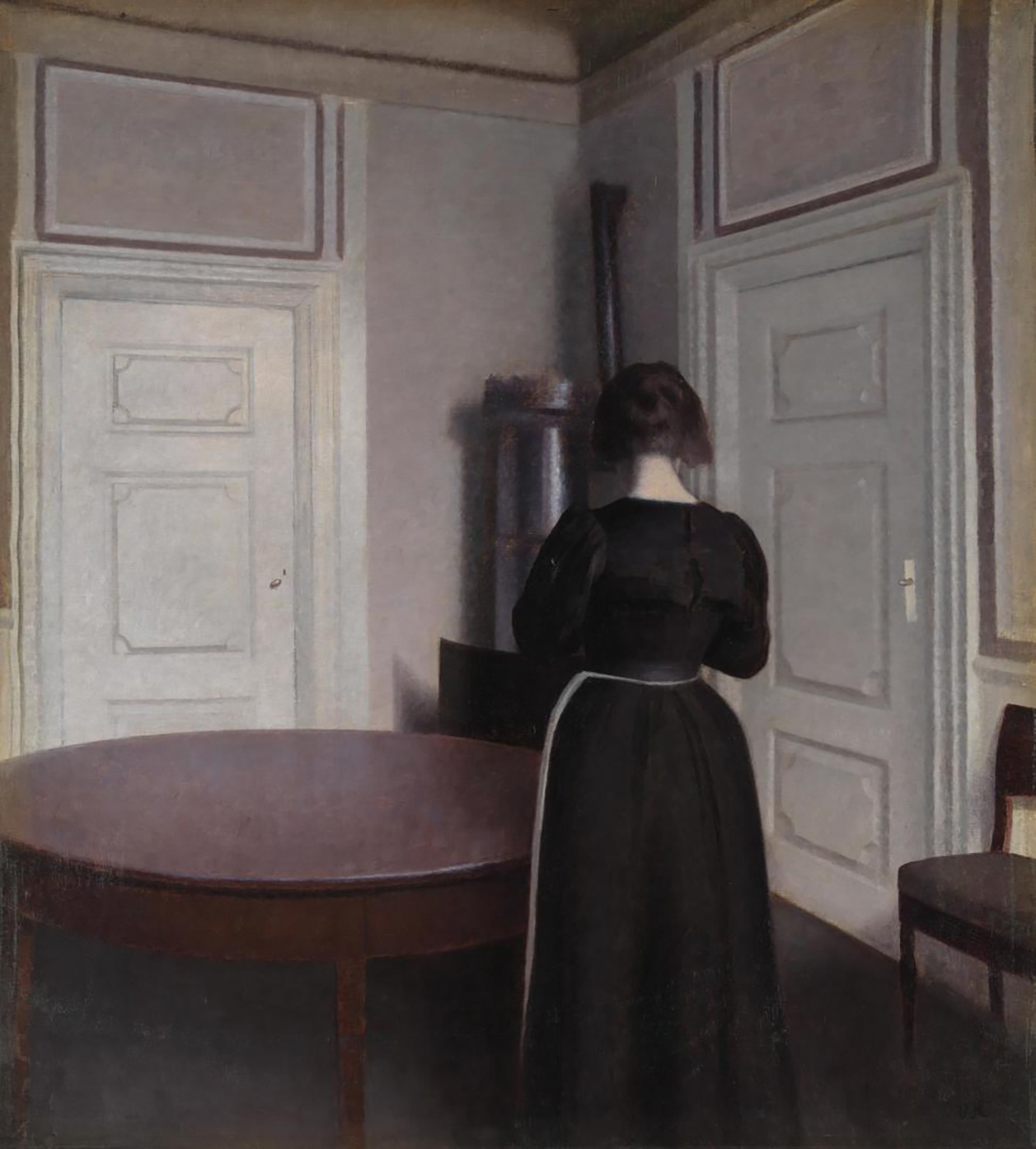

与《白画林》相隔三年后,在完成于2015年的《两位来访者》中,背景被处理成最简单的灰色墙面,两位并肩背向观众而立的女性形象几乎保持了完全一致的姿态,二者之间的差别仅有她们各自站立的位置,和朝向墙面微弱的角度偏移。画中空间被保持在一种仿佛趋于永恒静止的凝滞状态,人物的姿态如同雕像,甚至连她们的手臂、裙角也遵循相同的重力作用而自然下垂,毫无波动,像是被隔在博物馆的玻璃展柜背后而远离日常时间的侵扰。画中人可能被认作“不合时宜”的、沉思的古典状态以及画面的写实风格,将我们带回一个按理性原则建筑起来的,以真实为鹄的的世界。黑色的衣衫、蓝色的裙摆与灰色背景之间的对比与协调,简括而微妙的光影,克制而富于暗示性的人物背影于构图中浮现,这一切不免令人联想到维米尔或哈莫修伊(Vilhelm Hammershøi)的室内画杰作。只是这真实的表象已经被不动声色地掀开一角:正是在人物投于灰色背景的,看似平常的影子中,细心的观众会觉察到悖谬之处,乍看上去是并肩平行于墙面站立的二人,但从她们各自头发和背部的反光,以及脚下阴影投落和蔓延的形状,能推断出她们身后的光源并非出自一处,换句话说,按照现实的物理法则,我们能从光影的分布猜想眼前身影其实都来自同一人,只是分处不同的时空,被同一个画面自然而然地缝合在一起。

Three years after “White Painted Forest”, “Two Visitors”, completed in 2015, presents a background treated in the simplest manner with a grey wall, and two female figures standing side by side with their backs to the viewer in almost identical postures, with the only difference between them being their respective standing positions and the slightest of angular shifts towards the wall. The space in the painting is kept in a state of eternal stagnation; the figures’ postures are like statues, and even their arms and skirts follow the same gravitational force and hang down naturally without any fluctuation, as if they were isolated behind the glass cases of a museum, far away from the intrusion of ordinary time. The classical state of contemplation of the people, which might be considered “anachronistic”, and the realistic style of the images bring us back to a world built on rational principles. The contrast and harmony between the black dress, the blue skirt, and the grey background, the simplicity and subtlety of the lights and shadows, and the restrained and suggestive backs of the figures in the compositions are reminiscent of Vermeer’s or Vilhelm Hammershøi’s masterpieces. But the surface of reality has already been revealed: it is in the seemingly ordinary shadows on the grey background that the attentive viewer will notice the paradox of what at first glance appears to be a pair of people standing side by side and parallel to the wall: from the reflections in their hair and backs and the shape of the shadows falling and spreading at their feet, it can be deduced that the source of light behind them does not come from a single source: in other words, that, according to the physical laws of reality, we can infer from the distribution of light and shadow that the figures in front of us ,naturally sewn together by the same picture, are actually from the same person, but standing in a different position at a different time.

Two Visitors 两个来访者 oil on linen, 130x180cm, 2014

Vilhelm Hammershøi-Interior,1899.Oil on canvas, 64.5×58.1cm National Gallery, London

某种微妙的解读线索,在看似不经意间透露出来:薛若哲同年完成的一张小画《快到了》(2015),于灰色背景上并列描绘了两只几乎一模一样的手,除却姿态上有些微差别。手腕上的红绳也似在暗示这不过是同一只手。标题告诉我们,“快到了”,那么,我们看到的是时间切片的叠压吗?通过一只手的运动,时间在图像平面上被转写为不连续的位移? 在薛若哲的绘画序列中,我们经常遇到这一类相似的母题。诚然,对于熟悉了电影电视等运动影像媒介的当代人来说,目睹同一对象在相邻的两个时间切片中些微的偏移之姿,被叠加进同一个图像平面,已经不再是费解或鲜见的经验。然而,我们依然无法从类似迈布里奇图像那样,通过线性时间切片的串连去读解薛若哲绘画中的这些场景,时间在这里并非呈现为连续的序列,而是以近乎自然主义的方式交叠进一个共时性的图像平面。它看上去是熟悉,甚至是古典的,但它所暗示的那种观看方式以及作为其基础的媒介条件和时间感知显然又是晚近才出现的。这种时序错位被含蓄地收敛在画面(貌似)自洽的空间逻辑之中,仅以其细节暗示内在于绘画本身,而往往被遮蔽和无视的那些悖谬与裂隙。

A subtle clue to interpret the works is revealed in a seemingly inadvertent way: Xue Ruozhe’s small painting “Almost There” (2015), completed in the same year, which depicts two almost identical hands juxtaposed on a grey background, with only some slight differences in gesture. The red cord on the wrist also seems to suggest that these are the same hand. Yet does the title “Almost There” imply we are seeing a superimposition of slices of time? Is time transcribed as a discontinuous displacement on the image plane through the movement of a hand? In Xue Ruozhe’s painting sequences, we often encounter similar motifs. Admittedly, for contemporary audiences who are familiar with moving images such as film and television, witnessing the same object in two adjacent time slices slightly shifted and superimposed into the same image plane is no longer a puzzling or uncommon experience. However, it is still impossible to read these scenes in Xue Ruozhe’s paintings through a series of linear time slices, where time is not presented as a continuous sequence but rather overlaid into a co-temporal pictorial plane in an almost naturalistic manner in the same way as Muybridge’s images. It looks familiar, even classical, but the way of looking at them, their economy of means and the perception of time that underlie them clearly point to a more recent origin. This temporal dislocation is implicitly contained within the (seemingly) self-contained spatial logic of the pictures, suggesting only in its details the often obscured and ignored paradoxes and fissures inherent in the paintings themselves.

Nearly There 快到了 45 x 55 cm, oil on canvas, 2015

如此例证不难找到:《持续的观看》(2015)、《一个透视短缩的平面》(2016)、《体操》(2017)以刻意强调的透视,在画面中制造一个连续的、“真实”空间,于是,重复出现二次的人物形象,也因为透视所建立的前后关系和运动方向而给观者带来一种接近观看动态影像的错觉。然而,绘画本身仍是这里毋庸置疑的至高法则,视觉策略的运用并非为了让静态媒介摹仿动态影像,而是在两种甚至多种媒介的混杂乃至临界状态中撬动图像的裂缝,让固化的现实感知发生震颤:《体操》将前后两位女性的裙、鞋、袜处理成同脚下木地板一样的深棕色,而将她们的上衣施以房间墙壁一样的灰白, 墙壁和地板之间的分界线恰好从她们的裙腰处分别穿过,形成一道连续的折线——她们首先是,也必须是画中人,她们的存在是根据绘画的逻辑而决定的,其余或许只是巧合。《持续的观看》则给出了意味深长的对照:手持望远镜的主人公脚下并没有阴影,而她们身后腾起的浓黑烟雾则像现实中的实体一样在地面投下弧形的影子。在新近完成的《由白至白》(2023)中, 人物投影的色调暗示出营造出空间位置关系,但正如题目告诉我们的,这不是两个身着白衣的女性在渐次走向白色墙壁,这只是从“白”到“白”。“白”首先作为油画语言中的基础元素存在,它赋予墙壁、地板,衣裙以最丰富的变化和表现力。它是画面中世界的起因,也是其归宿。

It is not difficult to find such examples: “A Continuous Look” (2015), “A Forshortened Cliff” (2016), and “Gymnastics” (2017) use a deliberately emphasised perspective to create a continuous, ‘real’ space in the picture so that the repeated figures also give the viewer the illusion of almost viewing a moving image, because this perspective established a back-and-forth relationship and a direction of movement. However, painting itself is still the undisputed and supreme law here, and the use of visual strategies is not intended to make this static media imitate moving images, but rather to pry open the cracks of the image in the combination or tearing apart of two or more phenomena, and to make the solidified perception of reality tremble. In “Gymnastics”, the blouses of the women are painted in grey like the walls of the room. The line of demarcation between the walls and the floor passes through their skirts at the waist, forming a continuous fold – they are and must be, first and foremost, figures in the painting, whose existence is determined by the logic of the painting, and the other elements are, perhaps, here by coincidence. “A Continuous Look” (2015), on the other hand, offers a meaningful contrast: the protagonists holding binoculars have no shadows at their feet, while the thick black smoke rising behind them does cast curved shadows on the ground like if it was real. In the recent painting “White to White” (2023), the tones of the figures’ projections suggest the creation of a spatial relationship, but as the title tells us, these are not two women dressed in white walking towards a white wall, it is just a movement from “white” to “white”. “White” exists first and foremost as a basic element in the language of oil painting, which gives walls, floors, dresses, and skirts rich variety and expressive power. It is the cause and the goal of the painted world.

A Continous Look 持续的观看 200 x 250 cm, oil on linen, 2015

Gymnastics体操, 2017, Oil on linen, 200x180cm

A Foreshortening Cliff被透视缩短的悬崖, 2017. Oil on linen, 250 x 200 cm

White to White 由白至白, 2023. Oil on linen, 200x170cm

“绘画本身就是一种虚拟语气。我所做的,并非直接摧毁这个系统,而是深入到系统中去。”薛若哲在一次访谈中曾如是说。在另一篇创作札记中,他以回忆自己在看到马格利特原作后的失望为引子,细述了关于绘画思考的林林总总。 他发现,当画面把所有信息都摆在前端,绘画本身就会被推后和压扁,仅仅成为图像媒介之一,而失去了其固有的、特殊的感觉强度。绘画的母题总是或简单或复杂,而用什么样的方式,以什么样的状态进入绘画,以及如何将自我压进画面,这些问题同样重要,甚至更加接近画家秘密的核心。 任何一种历史上的视觉形态总要消逝,但绘画自身的历史总是以画家本人独一无二的肉身、心灵和手眼在不断地、鲜活地延续。薛若哲从文艺复兴早期作品中看到共鸣,他在附中时期开始大量临摹拉斐尔——安格尔——德加一脉的绘画,来习得一种凝练而微妙的造型倾向,近期则通过研究17世纪弗兰德斯和西班牙绘画来发展松动与多样的颜色表现。熟稔地运用技术,在他而言是为了解决具体问题:如何用油画这样具体的造型系统来表现中国绘画中非常重要的留白与空无,又如何在保留其绘画性的同时,来消解掉油画相较于摄影等平面媒介所固有的强烈物质感、视觉上的过于肯定和“前进感”,等等。同样,他对于“背影”的偏好,与其说是某种象征意义的寄托,更多是看中其固有的含蓄,暧昧和不确定性,在传达姿态、颜色、笔触等微妙细节的同时,可以进行有限度和更加克制的叙事。在薛若哲的绘画实践中,技术和造型并不直接关联于观念,毋宁说是提供了一个距离,让观念或符号这些过于显豁的,直接同语言勾兑的部分重新沉潜入绘画的内部。

“Painting itself is a fictional mode. What I do doesn’t destroy the system, but goes deeper into it.” Xue Ruozhe has said in an interview. On another occasion, he recollects his disappointment after seeing Magritte’s work in person, detailing a forest of thoughts about painting. He found that when all the information is on the image level, the painting itself is pushed back and flattened, becoming just one of the pictorial mediums and losing its inherent and special intensity of feeling. The motif of painting is either simple or complex, but how to enter the painting process in a certain way and specific state, and how to impose oneself into the picture, are as important as the theme, it is even closer to the core of the painter’s secret. Any kind of visual form will fade away in history, but the history of painting will always last constantly and vividly with the unique body, mind, and ocular relationship to the painter. Seeing a resonance in early Renaissance works, Xue Ruozhe began to copy a lot of paintings and drawings from the Raphael-Ingres-Degas lineage during his high school years to acquire a concise and subtle modeling technique. More recently, he has developed a loose and varied use of colour through the study of 17th-century Flemish and Spanish paintings. He is familiar with the techniques necessary to solve specific problems: how to use a modeling system as particular as oil painting to express the void and emptiness that are crucial in Chinese painting, and how to retain its painterly nature while at the same time dissolving its strong sense of materiality, or again the visual certainty and the “directness” inherent in oil painting as compared to two-dimensional mediums such as photography, etc. Similarly, his preference for “backs” is not so much due to its symbolic value, but more to its inherent subtlety, ambiguity, and uncertainty, which allows for a limited and more restrained narrative while conveying subtle details of gesture, colour, and brushstroke. In the painting practice of Xue Ruozhe, technique, and modelling are not directly related to concepts, but rather provide a distance for concepts and symbols, which are too explicit and directly synonymous with language, to re-dive into the interior of the paintings.

也是在这个基础上,我们得以重新看待薛若哲绘画中那些压缩的时间与纠缠的空间——不是为了制造错觉、悖谬和暧昧气氛,而是借以呈现和讨论绘画本身。“有人以为我做得是具象绘画,这并不准确, 我在做的是关于具象绘画的绘画。我希望保持一些距离。或许这就是虚拟感受的来源。” 从《被取消的风景》(2015)开始,作为背景的风景和作为主体的人物以貌似平滑实则暗藏玄机的方式被缝合在一起,于无声中模糊和动摇图像内部的秩序。画中人脚下投影不自然的角度,似在暗示她们所踏入的或许并非真正的野外风景,而是一幅绘有风景的幕布。而在《开弓》(2021)组画中,人物姿态沿用西方古典绘画中用于表现贵族伟岸的射箭图式,而背景亦是此类肖像常见的辽阔场景。画中女性的手臂紧绷,但手中并无一物,两张同等大小尺寸的画幅分别处理成横向与纵向构图,人物一侧一背。横构图中人物伸出的手臂投下似是而非的淡淡阴影,而在竖构图中,顺着她指尖去处,人们可以清晰地看到投射在苍茫云层上的一个身形轮廓。由此,“空间被拉回,重新成为一个图像,一个现代的工作室场景。” 而只有当我们在电脑屏幕上再度并列这两幅画面才会恍然大悟:横与竖构图中的风景其实是连续的,可以无缝对接。这些不断重复、呼应、回环同时又相互抵牾、戳穿和取消的视觉修辞术,在艺术家2020年以想象中的加州湾区为母题而创作的一系列作品中被运用得淋漓尽致。赭红落日、沙滩及海滨等集合了流行文化中加州印象的风景图式,全部通过第三方的工具,入如镜子、沙盘、屏幕或是舞台剧的布景等嵌入画面之中,并折射到画中人的视线之内。 或许我们会联想到,在具象绘画失却了作为视觉表征媒介的绝对权威之后,摄影、电影、电视影像也面临失效,媒介的竞争、更替与杂糅,正于人们无所觉察之际,以史无前例的速度改变着人类的观看、感知和现实体验。无所不在的数码编辑、图像处理和视效制作,让时空的嵌套、映射和压缩变得司空见惯。相反的则是具象绘画仍然于缓慢中保留着对于统一、封闭空间和单向、线性时间等原则的忠实信念,也正是因为此,当我们在观看薛若哲的绘画时,往往会有更强烈的“失真”之感,后者反而在电脑游戏、动画等生成/编辑图像中被自然地忽略。薛若哲在画面的各处都严格地遵循着具象绘画的基本法则,无论投影、透视、造型和色彩都务必力求准确,但当主体形象与背景、主体形象之间、作为内容的图像和作为物质的画布之间……当这些组成画面的局部以另一种秩序,另一种逻辑重新咬接起来,反而更为彻底地动摇了我们关于真实的连续性错觉,以及根深蒂固的观看习惯。 薛若哲总是在他的绘画中追求一种最小限度的,与日常状态的偏移,并在这几乎不被察觉的偏移中撬动最大限度的开裂,使绘画的平面拱起最幽深的皱褶。

It is also on this basis that we can re-examine the compressed time and entangled space in Xue Ruozhe’s paintings, which are not tactics to create illusions, paradoxes, and ambiguities, but are designed to present and discuss the painting itself. “Some people think I’m doing figurative painting, but that’s not accurate; my paintings are about figurative painting. I want to keep some distance. Maybe that’s where the feeling of artificiality comes from.” Beginning with “Cancelled Landscape” (2015), in which the landscape as a background and the figure as a subject are stitched together in a seemingly smooth but hidden way, silently blurring and shaking the internal order of the image. The unnatural angle of the shadows under the feet of the figures seems to suggest that what they are stepping into may not be a real landscape of wilderness, but rather a curtain with a landscape painted on it. In the group painting “Draw” (2021), the figures’ postures are inspired from the archery style used in classical Western painting to express greatness and nobility, while the background is the vast and empty void common to this type of portrait. The arms of the women in the paintings are taut, but there is nothing in their hands, and the two equal-sized panels are treated as horizontal and vertical compositions, with one figure showing her profile and the other her back. In the horizontal painting, the figure’s outstretched arm casts a faint shadow, while in the vertical composition, one can see the silhouette of a figure projected on the pale clouds if one follows her fingertips. Thus, “space is pulled back and becomes an image again, a modern studio scene.” It is only when we juxtapose the two images again on the computer screen that it dawns on us that the landscapes in the horizontal and vertical paintings are continuous and can be seamlessly intertwined. These visual rhetorical techniques of constant repetition, echoing and circling back and forth while simultaneously contradicting, puncturing, and canceling each other are employed to great effect in the artist’s 2020 series of works based on the imagined Bay Area of California. Ochre sunsets, sandy beaches, and waterfronts, all of which are clichéd images of California, are embedded in the images through third-party tools such as mirrors, sandboxes, screens, or theatre sets, and are refracted into the view of the characters. We perhaps may recall that after figurative painting lost its absolute authority as a medium of visual representation, photography, cinema, and television images are also now facing failure, and the competition, turnover, and blending of media are changing human viewing, perception, and experience of reality at an unprecedented rate without people being aware of it. The ubiquity of digital editing, image processing, and visual effects has made the nesting, mapping, and compression of space and time commonplace. On the contrary, figurative painting still retains in its slowness the faithful belief in the principles of unity, closed space, and unidirectional, linear time, and it is precisely for this reason that we tend to feel a stronger sense of “distortion” when viewing Xue Ruozhe’s paintings, which is naturally ignored in the generated/edited images for computer games, animation, etc. Xue Ruozhe strictly follows the basic rules of figurative painting in all parts of the picture, striving for accuracy in shadow, perspective, shape, and colour, between the figures and the background, between the figures themselves, between the image as content and the canvas as a substance … But when these parts that make up the painting are re-joined in a different order, in another logic, it shakes more thoroughly our illusion of continuity about the real and our deep-rooted viewing habits. Xue Ruozhe always pursues a minimal deviation from the everyday state in his paintings, and in this almost imperceptible deviation, he pries out the largest cracks, making the plane of the painting arch into the deepest folds.

Cancelled Landscape 被取消的风景 200 x 250 cm, Oil on linen, 2015

Draw开弓, 2021. Oil on linen, 90 x 120 cm, 120 x 90 cm

Guided Tour around Bay Area湾区导览, 2020. Oil on linen, 225 x 400 cm

Remote Landscape遥远的风景, 2020. Oil on linen, 110 x 62 cm

Final Solution 最终解决方案, 2020. Oil on linen, 110x85cm

2022年初,随着小女儿的降生,薛若哲开始了一个他计划“持续到生命尽头”的绘画项目“YYYY-MM-DD”。这个非同寻常的系列,反而为我们理解艺术家如何看待时间中的绘画以及绘画中的时间提供了切入口。每一天,差不多在同一个时间,在一瓶准备好的花束后面,薛若哲会支上画板,调好颜色, 写生其中一朵花,并在画面上用阿拉伯数字以年-月-日的通行格式标注下这一天的日期 。时间流逝,瓶中花在不停变化,从绽放,到凋谢, 从一朵花,到下一朵,花朵的整个生命历程被依次定格在画布上:只增添新的部分,不覆盖原有内容。 一瓶花画完后,他会再买一束新的鲜花插入瓶中 ,如此往复,日日如此。这些大小、比例、形制基本相似的,随时间不断增加的图像,将组成艺术家生涯中最漫长的一个序列,与其说它们是一帧帧凸显当下状态的写生快照,不如说它们是一座座由时间切片累压和层积而成的,对于消逝事物的纪念碑。绘画因此成为同时间打交道的方式,这是一门古老的技艺:就像我们在古罗马墓穴中力求写实的逝者肖像那里所看到的,画家以此来挽留那些被时间所定义、塑形、摧毁和湮没的生命。这也是一种不断更新的技术,时间在形象平面上被持续地重新编码:标注在每朵花旁边的,以“YYYY-MM-DD”格式出现的日期,仿佛在提示这个以抽象和计量面目凸显自身的当代时间秩序是如何渗透了最微细的生活角落,对生命——在这里是以一朵花的形式体现——日复一日的标注和重复,让人想起谢德庆以打卡的苦行来反抗这抽象秩序对生命的榨取。这些看上去简单,重复的花卉写生,因此成为多条时间线索、多种时间体制的交汇之处,古老的图像媒介同当代的数码化时间格式重合,自然时间、机械时间、被计算机技术推动其再度编辑、分解和重组的时间、以及生命和心灵于此感受、回忆和想象的时间……这一切通过叠加的图层和持续的行动,最终沉淀在一方小小的画布之上。在花与花之间色彩和姿态的差异之中,我们得以重新理解薛若哲绘画中那些看似修辞手法的重复,无论是同一幅画面中那些几乎相似人物和姿态 (带着轻微而不容忽视的差异),还是穿过不同画幅延绵、呼应、不断回返的主题和反复出现的形象, 似乎在告诉我们:时间并非某种外在于画面的东西,它其实一直潜伏在图像与图像,图像与画布的铰接处,那道通往不可见世界的幽深缝隙,而艺术家的工作正是在这交叠、游动和不确定的边界地带探险,让我们得以一瞥那最幽深处,生命本来的形状。

In early 2022, with the birth of his youngest daughter, Xue Ruozhe began “YYYY-MM-DD”, a painting project that he plans to “continue until the end of his life”. This unusual series provides an entry point for us to understand how the artist sees painting in time and time in painting. Every day, at about the same time, in front of a vase of prepared flowers, Xue Ruozhe will put up a canvas, mix the colors, paint one of the flowers, and mark the date in the format YYYY-MM-DD. As time passes, the flowers in the vase change, from blooming to wilting so that from one flower to the next, the entire life cycle of the bouquet is sequentially framed on the canvas: new layers are added without overwriting the original. When he has finished painting a vase of flowers, he buys a new bouquet and inserts it into the vase, and so it goes for days and days. These images, which are similar in size, proportion, and shape, and which increase in number over time, will form one of the longest sequences in the artist’s career. Rather than being a series of snapshots highlighting a momentary state, they are a monument to things that have disappeared, made up of slices of time that have been pressed and layered together. Painting thus becomes a mean of dealing with time, reminiscent of ancient techniques to measure time: as we see in the portraits of the dead in the catacombs of ancient Rome, the realism of the representations is a way for painters to preserve lives that have been defined, shaped, destroyed and annihilated by time. It is also a technique that is renewed constantly, in which time is continually recorded on the figurative plane: the date in the form “YYYY-MM-DD” next to each flower seems to suggest how this contemporary order of time, which manifests itself abstractedly and through its measurement, penetrates the tiniest corners of life and has an impact on the lives of those who live, as well as on those who have lived in the past. The day-to-day repetition of date-marking — here in the form of a flower — reminds us of Xie Deqing’s austerity in his habit of punching a time card to rebel against the exploitation/extraction of life by this abstract order. These seemingly simple, repetitive sketches of flowers thus become the intersection of multiple threads of time, multiple regimes of time, where the ancient medium of the image coincides with the contemporary format of the digitized time, where natural time, mechanical time, time edited, dissected and restructured by computer technology, and the time that we feel, remember, and imagine are combined … …All of this is finally deposited on a small canvas through superimposed layers and continuous action. Amidst the differences in colour and gesture from flower to flower, we are able to understand once again the repetitions of Xue Ruozhe’s paintings that appear to be rhetorical devices. Whether it is the almost identical figures and gestures in the same painting (with slight but noticeable differences), or the themes and recurring images that extend, echo, and return through different canvases, it seems to be telling us that time is not something outside the picture, but is always lurking in the image. It seems to tell us that time is not something external to paintings but has always lurked in the articulation between image and image, image and canvas, the deep gap leading to the invisible world, and the artist’s work is to explore this overlapping, wandering, and uncertain borderland, so that we can catch a glimpse of the deepest place, the original shape of life.

20220120-20220128, 2022. Oil on linen, 50x40cm.