THE ART OF RUOZHE XUE: Void and Intimacy

Jonathan Miles

“What cannot be tamed is art as silence. The position of art is a refutation of the position of discourse. The position of art indicates a function of the figure, which is not signified – a function around and even in the figure…. Art covets the figure, and “beauty” is figural, unbound, rhythmic.”

Jean-Francois Lyotard

Firstly it is possible to describe these paintings as presenting figures bereft of motion or at standstill. Any anticipation of motion, would be slow, very slow, a form of slowness coupled with the imaginary withdrawal of speech, so in a way, both silent and slow. From here it might be claimed that the condition of cinema or staged (cinematic) photography is close by, but this neither detracts nor adds to the condition of them as paintings. There are of course so many other things that are close by: the grey sky of Beijing, friends, cameras, art history, gestures, shadows, densities, speed, the tonality of faces and moods. Such a list could go on, but whatever, it is all part of the meditation on what is close and what is remote. The logic of this art is born out of the refractions of such difference: an art that refracts sense.

Hold,Tear 抓住, 撕碎, 190x145cm, oil on linen,2019

There are two paintings of feet with white tights that are simply called L and R (2019). The spatial interval means they are both in isolation but also coupled at a distance. On a formal level they might be viewed as an exercise in the control of tonalities, even a modest fugue in greys and white. The light captured around the region of the toes, are rendered in a creamy, glazed application of white oil paint, which both describes and releases the visible simultaneously. Perhaps in attempting to add all of this up, we might not be aligned with the state of transience that appears to pass through the grain of the visible.

L, 25x30cm,oil on linen,2019

R, 25x30cm,oil on linen,2019

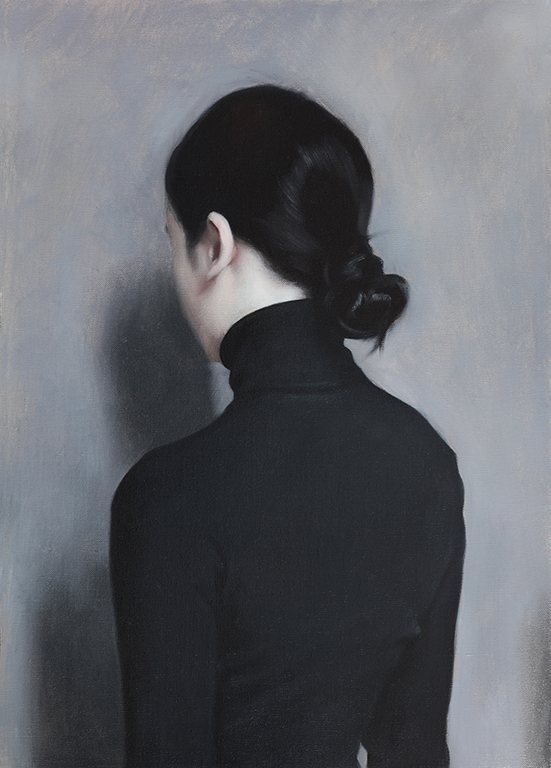

Returning to the cinematic, there is a striking relationship to ‘The Last Year of Marienbad’ (1961) by Alain Resnais and screenplay by Alain Robbe-Grillet. The characters appear to be locked within a time warp they cannot escape from and are thus left to glide around in endless configurations conflating memories of the past with anticipations of a near future (a future that refuses to arrive). At any given moment or passage it is difficult to discern what time zone is being registered so the film itself is like entering a labyrinth. In turn there is a hyper mode of spatiality in the fiction of Robbe-Grillet as if characters are being guided by an external abstracted geometry that strips them of subjective agency. An absent third person narrator (the husband) is a silent observer in his work ‘Jealousy’ (1957) as he watches his wife (named only as “A”) interact with her neighbour Franck. As the novel progresses the gap between observation and imaginary suspicion is closed. Without any direct links there are nonetheless shared traits especial in regard to the absent third person and the eraser of subjectivity. In many of the painting subjects turn away in order to face walls, or voids and even when frontally rendered they are in part in shadow. There is something closed down about each of such postures, the control in tonality of the palette aligned with the control in mood being exhibited. Not quite a universe of frozen solitude but certainly one in which affective modes of encounter are squeezed into a tight corridor of desire. Like the subdued tonality, there is nuanced passage of affect but one whose intensity is of cool subtraction. The art of Magritte and Delvaux might be evoked in this context but this would be to disregard the delicacy that is at play that takes this art way from the persistent theatrical staging of Surreality. It is not the a-temporality of the unconscious being explored, but rather the interval of the slow drift towards it.

Turning towards, turning way from, just repeated turns: there is little by way of progression. Perhaps it is impossible to add things up. Up close to things with nothing clearly to see, vision is restricted vision. Walls are in the way, shadow encloses: all the frames of visibility compress the subject. This in part explains why the gestural economy is so restricted.

Hovering Form of Two Pieces of Leather 两片皮的盘旋形式, 110x85cm,oil on linen,2019

In the work Untitled (2019) a female figure stands close to the wall in which her shadow is cast. The work of the Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershoi (1864-1916) might be evoked in the relationship of the subject and the circulation of light. In his work, light offered is also touched by the incline towards its withdrawal, so returning to the work in question there is both the certainty within gesture but this is coupled with a prevailing sense of evanescence. What is being offered and what is withdrawing from this, meets within the tonal mix of nothing much occurring but being drawn into looking for such an event of occurrence nonetheless. The art of painting is in the rendering of the yet-to-come within that which is not explicitly rendered. Surrealism was the over-determination of such a condition through its evoking of dream and the unconscious whereas an artist such as Hammershoi presents a state under-determination.

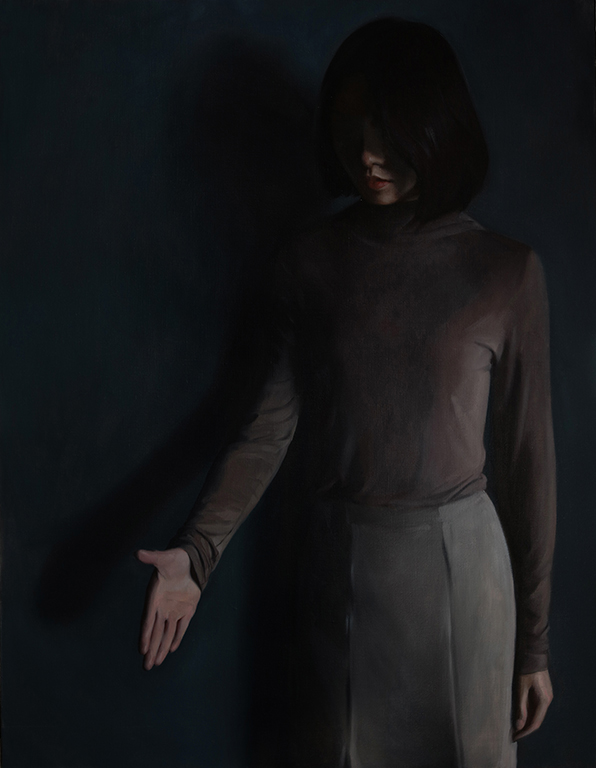

The persistence of looking away is perhaps linked to partial or fragmented objects not only as a source of observation but also anxiety. In ‘Still Life no.3’ (2019) we are presented with a seeming object of desire in a pair of shoes. The shoes are depicted with an invested textual vibrancy but they are connected to a truncated pair of plastic legs that serve as interruptions of any visual pleasure because they are uncanny partial objects. Pleasure gives way to anxiety because something does not quite fit because the body imaginary wholeness has been cut. In turn another form of cut is to be found in ‘Hovering form of two pieces of leather’ (2019) in which two leather dresses hang within space cut of from both their source of attachment and their context for hanging as a pair. This not necessarily uncanny but it does lead to the possibility of either misrecognition or anxiety as opposed to being a source of visual pleasure. This in turn creates a space of arrest between the poles of pleasure and displeasure and this is never resolved because of the way the figure of desire is being trailed as the invisible component of this art. This is exemplified by ‘Nevertheless” (2019) in which a female whose face is in shadow offers her hand in light to an un-figured other. Again we are being given over to a partial scene that cannot be completed within the imaginary. The potential warmth of the gesture is undercut by the visuality of being closed by shadow. What is offered renders the viewer in a state of suspension by not having the means of resolution, there is no way a revelation of understanding might arrive because there are no narrative clues whereby this might occur. Instead we are left to put aside the before and after of the event. Within this space characters appear as remote even though we might suspect they are close to the artist so might be solicited to look with this fracturing of sense; one close up and once at a remove. This dynamic is what provide these paintings with their dynamic of push and pull, and in turn their rhythmical accord that yield excess outside of any structuring of meaning. Such a structure of meaning is not so much erased as simply declined with an under-signifying economy that disavows narrative continuity. On a gestural level this attests to the feeling of not having the space to go on but going on despite this, of painting whilst standing on the tightening wire connected to desire.

StilllifeNo.3 静物3号,40x50cm,oil on linen,2019

Slow, slower still, a suspended slowness that presents a construction of a suspended interval. Vermeer, Friedrich and Hooper have in different ways explored the art of the suspended interval; Vermeer utilized this state in order to close the gap between interiority and exteriority, Friedrich to open out the spatial horizon so that infinity might be accessed by the perceiving subject and in Hooper’s case, to arrest temporal flux in order to frame a poetics of loneliness. In each of these different cases, light is the primary medium for having a world rather than language, thus seeing is actualised in advance of knowing. In all three cases there might be a common feeling of being on the edge of being able to articulate this imaginary gap, only then to fall back into being-with the rapture contained within (mute) visibility. Something looks back but in looking back a movement of desire serves to disrupt the ability to link visibility with discourse. This explains in part the feeling of being left on the edge or suspended in a state of reverie.

Nevertheless 然而, 86x111cm,oil on linen,2019

After the advent of the Chinese Revolution the training of artists assumed a Soviet realist model that in turn was based upon French academic realist models of the 19thC. Modernism was viewed as decadent but the Chinese Classical model was also retained under the slogan of letting “the old serve the new.” These models constituted in turn a memory system unlike the Western tradition of modernity that was anti-mimetic. After the economic reforms of the early 80’s contemporary art gradually found entrance into the art of academy. Xue’s aesthetic formation derives from a synthesis of these different memory systems as he trained in the art of calligraphy, realist-mimetic painting and also studied painting in London. This partly explains the slightly elusive quality of this as an art. On the surface everything is in place on the level of syntax, context and gesture but the uncanny emerges from within this surface of presentation. In evidence is a subdued optics, combined with constricted spatial depth in which the incline of memory and the unease of the imagination are brought together, even to the point of conflation. That something has happened, or is about to happen, is not rendered as apparent. This is all symptomatic of the feeling issued from an idea of late time of restricted gestural economy. In Hold, Tear (2019) a figure is cast double. The tonal poetics derive from the night that never quite arrives. The space between the two is measured to the point of aloof distance but then they are not apart because they appear as being the self-same. Is this double an outcome of spectrality? Hands held behind the back, faces turned way, light touching the nerve of withdrawal point towards a deeper mode of displaced presence. It is a dark painting both on the level of tone and mood but a painting issuing out of a compelling lightness of touch; a fold of tone and touch. This is what we are given over to, the art of tone and touch evading common sense. Evasive: it simply goes on.

From one moment to the next, light still passes through; things or postures repeat, but repeat within delicately nuanced difference. These painting ask of us to attend to, to be with, in the in-between within intervals of time that are outside of everyday temporality. Something is close-at-hand; we are offered this something passing over, or at the cusp of passing over, into yet another state outside of presence. Incline and declines, offering and withdrawals, entry and exits, we are placed in touching range of that which eludes, a third person mode of seeing perhaps. The quiet drama has no outcome but instead simply resolves to go on, not as in a grim treadmill or as aesthetics of loneliness or of waiting, but in order to keep open a more delicate space of becoming, becoming marked not by the absence of time, but the interval that rehearses the arrival of the condition of an opaque outside. This might sound like a nervous art but rather it is an art that retain its nerve, lets us breathe with its interior, slowly but surely expanding the capacity to breathe within images of an evasive outside.

Jonathan Miles is a tutor in Critical & Historical Studies and Fine Art research in Royal College of Art, London; a writer both of theoretical essays and fiction; as well as being a painter.

Untitled 无题, 50x70cm,oil on linen,2019